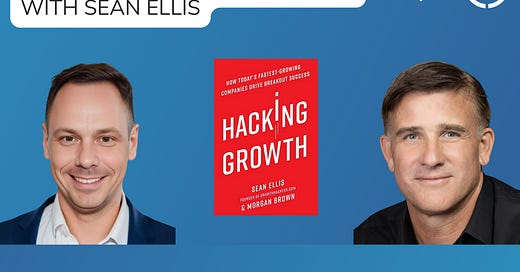

Growth Hacking: The Science of Growth with Sean Ellis

Sean's high-velocity test/learn process has accelerated growth at companies like Facebook, Airbnb, and Dropbox. He coined the term growth hacking and popularized the North Star Framework.

Hey, Paweł here. Welcome to the free edition of The Product Compass.

Every Saturday, I share actionable tips and resources for PMs.

Here’s what you might have missed:

Premium: How to Ace Your First PM Interview

Free: PM Skills Assessment (Analytics, Metrics, Experimentation)

Premium: 12 Laws of UX Every Product Professional Should Know

Premium: The Product Frameworks Compendium (35)

On Thursday, I will publish a new Skills Assessment. To prepare, you can review posts and top-recommended videos related to Product Discovery.

The Science of Growth with Sean Ellis

Product growth is simple.

But it's often misunderstood and poorly applied.

That's why I'm excited to share my interview with Sean Ellis, the author of the international bestseller Hacking Growth.

His high-velocity test/learn process has accelerated growth at companies like Facebook, Airbnb, and Dropbox.

Sean coined growth hacking, invented the ICE prioritization, and popularized the North Star Framework.

My favorite insights

Growth hacking is not about testing random ideas. It's a systematic process of testing and analyzing data to unlock growth.

It involves not just acquisition but also activation, engagement, retention, and revenue levers.

You need to understand customer needs and how the product meets them.

Product-market fit is essential. In the episode, Sean explains how to measure it easily and why you should also understand the "Why" behind it.

Align messaging with the reasons customers love the product. And bringing the right customers to the right experience quickly.

Your goal should be to ensure long-term sustainable growth, not just quick, short-term gains.

Without cross-functional alignment and a shared understanding of the North Star Metric, everything falls apart. Sean explains how to build this alignment.

In many companies, opinions are stated as facts. Instead, state them as hypotheses, develop and maintain testing habits, and reinforce a data-driven approach.

The same scientific process and principles can be applied to B2B products. Understanding the end users' value is critical.

The full episode

In this episode, we discuss:

(01:29) What is Growth Hacking?

(02:41) The required skill set.

(04:48) What's required to start thinking about product growth?

(06:17) How can we measure product-market fit?

(08:48) How can we accelerate growth? Understanding growth.

(12:10) Refining value proposition. The right customer. The right experience.

(18:08) The science of growth. Growth process. ICE scoring.

(22:24) The power of experimenting.

(23:58) Creating value vs. capturing value. How everything is connected.

(26:28) What can go wrong? Building alignment. Becoming a growth leader.

(32:56) Building the right culture. The testing habit.

(36:25) North Star Metric and the physics of growth.

(41:19) B2B vs. B2C product growth.

Where to find Sean Ellis?

Sean’s LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/seanellis/

Sean’s website: http://www.seanellis.me/

GrowthHackers community and courses: https://growthhackers.com/

The transcript

Pawel (Host): Hi, welcome to the Product Compass podcast. My name is Pawel Huryn. Today my guest is Sean Ellis, the author of the international bestseller "Hacking Growth," with over 1 million copies sold. Sean popularized the North Star Metric, and his approach propelled breakthrough growth at companies like Facebook, Airbnb, and Dropbox.

Today, we discuss what growth hacking is, implementing the high-velocity test-learn process, building and reinforcing the right habits, and the scientific approach to growth. Are you ready? Great, so let's get into it right now.

Sean (Guest): Thank you, I'm excited to be on with you to tell you about growth, and I'm excited to have you on.

Pawel: Sean, you are the founder of Growth Hackers, co-author of "Hacking Growth," and you've been the growth marketing leader at many companies whose valuations exceed $1 million, like Dropbox, Eventbrite, LogMeIn, and Lookout. You also coined the term "growth hacking," which you used to ignite massive growth at those companies that they mentioned. So I thought that maybe we can start with the question, what is growth hacking and maybe what it is not.

Sean: Sure, the simplest definition is that it's taking a rigorous process of testing and analyzing to unlock growth in a business. So, you could potentially say that really just describes marketing done well these days. The other place that for growth hacking to be effective is that you're doing it not just on the customer acquisition side. You're doing it across really all of the levers of growth, so acquisition, new customer activation, engagement, and retention, how do I keep customers coming back, how do I get existing customers to bring in new customers, even optimizing the revenue model, and all those levers kind of working together through that test-learn process to improve growth as much as possible.

Pawel: Are there any competencies that you need to start? You mentioned marketing, pricing, there's acquisition, there's retention, we need to activate customers. So, I imagine we need many competencies from different areas to ignite this growth.

Sean: Yeah, so you mentioned some of the companies that I had worked with, and so in most of those companies, I started out as kind of the only guy who was doing it. Dropbox was less than 10 employees when I was there, everyone else was core product. So, obviously, I needed a lot of skills. As teams grow, then I could hire some of those skills and become more specialized. So, I'd say for an early-stage startup, you probably want to have one person that's fairly dynamic and can do a lot of things. At the very base, I think that the most important skill is probably discipline to follow a process and then somewhat analytical so that you're actually able to see what works, and then creative in the sense that you're coming up with ideas of things to test. Ideally, you're not just randomly coming up with ideas; they're based on talking to customers or somehow processing customer insights. So, you need to be somewhat curious on the customer side as well, so those would be the base.

Pawel: You mentioned many topics I would like to ask you about. I can relate to this experience because I was also running a startup. I remember doing everything from many different areas, so at the beginning, before we hired more specialists, it was pretty challenging. Are there any prerequisites to start thinking about growth and scaling your company? Can you do it any time?

Sean: Yeah, I mean, so start thinking about growth, you can, you should really start from day one. And that's kind of like, you know, does anyone need what we've built? Let's go out and talk to some customers and see how they solve the problem we're trying to solve today. So, I think you're thinking about growth from pretty early on, but the prerequisites for actually executing that test-learn process, that growth hacking process, you want to make sure that you have product-market fit.

And I'll explain, so you essentially have a product that is a must-have for some segment of users that you can go out and reach. So, if there's a group of users that say, once they try the product, they say, "Wow, I really need this product. I'm gonna keep using this product," then you have the prerequisite to say, "Okay, now I need to be aggressive about getting a lot more people to come in and try it."

Pawel: You mentioned segments, and you mentioned people saying that they would like to use the product. So, is there any way that you can actually measure or test that you achieve the product-market fit?

Sean: Yeah, there's a couple of ways. So, one, the most accurate way to measure it is if they keep using the product. So, we call that a retention cohort. So, for every hundred people who come in and try the product, over a period of time, are they continuing to use it? And so, you're never going to have all 100 people stay on the product. So, after a few hours or days, depending on the kind of nature of the product, you're going to lose some percentage of those people. But what product-market fit looks like is that eventually, you get to a point where, say, three or four weeks into it, I still have half of the people who tried it, and they're using the product. And then I look two months later, those half of the people are still using the product. So, you're able to retain some percentage of the people who try the product in the long term.

So, that's the problem with that approach to validating product-market fit is that it could take you several months to be able to see what happens to those retention cohorts. So, I came up with a question that's probably almost 15 years ago now, which was, if I just ask the people who are using the product, how would they feel if they could no longer use the product and gave them a choice: very disappointed, somewhat disappointed, not disappointed, or even not applicable, I already stopped using the product. If people say they would be very disappointed without the product, there's a very good chance they're gonna keep using the product long term. And so, that's a way to get kind of a shortcut way to figure out who am I likely to retain.

Of course, if they say they're going to keep using the product and they actually stop using it, their behavior is more important than what they're saying. And so, that's why I say it's more accurate to actually use retention cohorts to make that decision. But you get a faster read by just asking that survey question.

Pawel: Yeah, I like this distinction between what people say and what people actually do because this is common in product discovery that it's not necessarily the case that what people say is what they will do in the future, right? So, let's say you achieved the product-market fit through those retention cohorts. You see that customers are staying, retaining, and using your product. What can we do next to accelerate this growth?

Sean: Yeah, so the next thing I want to do is not just have product-market fit but actually understand it. So, that's where I want to be able to narrow down to see exactly who says they'd be very disappointed without the product. So, the benefit of using the survey approach is that you can really start to dig into some qualitative information a lot more. Where if you're just using retention cohorts, you don't necessarily know why they're using it or what they were using before. But with a survey, you can add other questions where you start to identify, okay, there's a lot of people who try the product who stop using it right away. What are the characteristics of those people versus the ones who actually keep using it? So, you start to identify who's my target customer.

And then you can also figure out, this is probably the most important question when I do the survey, is asking them what is the primary benefit that they get from the product. And so, if I'm running, if I have a lot of early users on a product, then I can kind of do it across multiple surveys. So, I'll start with an open-ended question, so like get write-ins from a lot of people. And then, that gives me an idea: what are the main patterns I'm seeing there?

And then, I'll narrow it down to giving people the next group of people a choice of three or four different benefits that they could choose from. But once I know what the core benefit is, and then I can drill into understanding why that benefit's important to them, I can focus on messaging that highlights that benefit. So, I'm actually setting the right expectations about what the product is going to do for people. And so, if you contrast that to a mistake that I see a lot of people making is that they'll think, okay, growth hacking is about testing, so I'm just going to A/B test a whole bunch of messaging. And maybe they end up finding a message that gets a lot of people to sign up for the product, but that message isn't related to why people ultimately end up loving the product. And so, you start attracting the wrong type of people.

So, it's better to figure out okay who loves the product, why do they love it, let me build a set of messaging that highlights those key benefits of the product's really good at delivering. Now, I'm acquiring the right type of people. The next question is, how do I get those people the right experience inside the product? And that's a lot of what the onboarding becomes about, you know, ultimately what's the first time they really experience that core benefit. We would call that the aha moment.

And so, if you can get a new user where you've set the right expectations and now you streamline their ability to use the product in the right way and experience that benefit, you're much more likely to long-term retain that customer. And so, I spend most of my early time getting the messaging right and getting the onboarding right to get someone to the right experience in the product as quickly as possible.

Pawel: Okay, so on the one hand, we have this feedback loop on the value proposition because, from my perspective, when you start building a product, you should already assume what is your value proposition and talk to the customers and define what the value proposition will be and which problem you will solve. But then you get this feedback from the customers after they start using the product on what the actual main benefit is for them, and then you can refine your strategy, right?

Sean: Yeah, I actually have a great example about that where I worked with a mobile security application years ago, probably almost 15 years ago now, where I asked the question, how would you feel if you could no longer use the product? And only six or eight percent of the people came back and said that they would be very disappointed without the product. And so typically what I was seeing is like for Dropbox or Eventbrite some of the companies I worked on before it was you know 40, 50 percent of the people saying they'd be very disappointed.

So I saw that that 8% and I was, I was like oh crap this, this is probably not a company I should have have committed to. But what we were able to do was study the 8% who said they'd be very disappointed, do exactly what we just talked about and, and essentially reposition on that benefit and then, so just with a slight message change and then a little bit of the onboarding.

So, the product did three or four things but we, there was only one that people really were focused on so it was an anti, an antivirus functionality. There was a suite of security tools but the antivirus was actually what people valued the most. And so we streamlined the onboarding to that, so that that's pretty easy product development, we didn't have to develop something new, we just had to hide some things in the onboarding.

And then we surveyed the next group of people who went through this new signup flow with different messaging and quickly getting into setting up antivirus and it was, it was 40%, so it only took us like two weeks to move from 8% of the users considering that a must-have to 40% and then six months later it was at 60% of all users said they'd be very disappointed without the product. And it was probably within about two or three years from then, the company was in the press at raising around a financing at a billion dollars. So I think it's, it's one of those things that, you know like I said I almost quit the role when I saw how undervalued the product was from those early users but once we figured out what the product was truly great at delivering, we were able to build a flywheel of growth around setting the right expectations and getting people to the right product experience.

Pawel: Yeah, I love the example. Did you also target this product to different customer segments, or was it just a different onboarding process?

Sean: No, I mean in a sense the messaging, the messaging became a filter. So you know and that's where again the mistake of just AB testing for the highest response rate can maybe attract the wrong people but by focusing on the benefit the product was truly great at delivering, people who weren't interested in that benefit bounced, they didn't sign up.

So it was only attracting the people who were interested in that and that's so, so in a sense we targeted different people because we converted different people but we didn't change anything in terms of the channels that we were targeting at that point. It was a fairly organic growth engine, so we couldn't, there wasn't a lot we could do to change the people hitting the website anyway.

Pawel: Yeah, that's interesting. I had a different experience with sales targeting as many customers as possible and grasping every opportunity on the market just to increase sales and then it turns out that only some small customer segments, those are our key customers that we make actual profits on and the rest is then it's churn and or they are not satisfied with the product.

Sean: Exactly, and that's why when we're talking about like the prerequisite for growth being product-market fit, product-market fit essentially means that you've identified the right type of customers and the right experience on the product that makes it a must-have. And so if you, if you aggressively try to grow before you've done that, you're going to do exactly what you just said, you're going to, you're going to cast too wide of a net, promise the product being everything that anyone could possibly want and then have a frustrated sales team or just a bad conversion rate of people who maybe you're actually able to convert them in the short term but they all stop using the product after 30 days because it just doesn't meet their needs.

And so, so that's the key is just figuring out what is that, what is that use case for the people who really need the product and how, how I get those right people using the product in the right way and that's going to lead to a retained customer base that ultimately allows you to build a sustainable growth engine.

Pawel: Yeah, amazing. So it's not just about testing random ideas and checking what works, but actually, some work is required before you start investing in scaling. So that you understand the problem you are solving and then you can think about solving this problem or maybe improving in some areas.

Sean, you mentioned a growth process. Could you quickly tell me how it works?

Sean: Sure. I'll even kind of back up a little bit on, you had mentioned I coined the term growth hacking and so a lot of people also then say you invented growth hacking. But ultimately, growth hacking is just simply the scientific method that has, you know can trace its roots to ancient Greek times and it's, it's you know about having, we learned most of us learned about the scientific method when we were in school and it's about having a hypothesis and you test that hypothesis in an experiment and then you learn if the hypothesis were true or not. Really the process that we're talking about here. So, most of the time the scientific method is applied to like innovation, you know trying to figure out you know a cure for cancer or you know whatever, whatever the, the you know you're trying a lot of things to try to achieve an outcome. In this case we're trying to achieve a growth metric, generally. It might be like a conversion rate if it's, you know a specific point in the funnel. But we're, so we are also innovating here. We're coming up with better ways to attract, convert and retain customers.

And so that's, that's, you know you want to generate a big backlog of ideas. So it all starts with a recognition that probably every single thing you're doing, you started with someone's guess of this is, this is how we should do the messaging on the page, this is how we should make the signup process, this is how we should have someone get started with a product. And the chances that those guesses are the best possible way you could do something is, is basically zero. And so the only way to drive improvement on those initial guesses is by trying a bunch of things.

And so you come up with a lot of ideas of the things you could potentially try. You need a system for prioritizing which ideas that you want to run. And so I came up with a scoring system years ago probably six or seven years ago called ice scoring where each idea is scored on its potential impact, and then so if it's successful how impactful will it be on the business or the or the objective. And then confidence, how, how confident am I that it will be successful. Do we have some, some evidence that suggests that other tests like this worked or with some customer research that says okay this test is really solving something that customer's struggling with. But kind of scoring that on a on a scale of one to ten.

And then the last one is ease. So ease is just how easy is it to run this test. And, and the ease you know is, is going to often be around the team's creativity. Like there's always a more complicated way to run a test and so what's sort of the simplest way you can run the test where you're going to get a, a pretty accurate result. And so you know you may initially say oh gosh on an e score this is going to be, this is not going to be very easy. We're going to give it a a low e score of say a two or a three.

But then someone says wait if we just did it this way we get the answer and that's actually really easy to implement. So maybe it then goes up to an eight or a nine. So what you're trying to do is have ideas that are, uh, very high potential impact and then uh you have a lot of confidence it's actually going to work and they're really easy to test. And so those are probably the types of ideas you want to run first.

Pawel: So, the amount of tests that you run regularly, I guess this is important, right? So that it elevates the speed of how fast you can learn.

Sean: Yeah, like Jeff Bezos said, Amazon has a great quote, he just says, “Our success at Amazon is a function of how many tests we run per day, per week, per month.” And so, you know, the former CEO, the founder of Amazon, but he's like goes back and forth as being the richest person in the world and uh and you know one of the most successful companies in the world and he's literally saying their success of that company as a function of how many experiments they run.

And so I think all of us should should look at that and say how do we run more experiments to increase our ability to learn more quickly about what works and doesn't work to drive value for customers.

Pawel: I previously noted the specific question about ICE score. Is effort the effort of testing the idea, is it the cost of implementing the whole idea or is it the cost to run a test like a simplified version of idea, maybe a prototype, maybe a feature stub?

Sean: Yeah, it's to get the answer. So the answer is going to be, you know, what's what's the simplest way you can implement that idea to figure out if it works. Once you have the answer, the the long term, you know, maybe maybe it requires some some fairly heavy investment to to capitalize on that answer and make it a long-term contributor to the growth engine but uh the the the E should be around, is it is it easy to figure out if this uh makes a difference or not to the business.

Pawel: There's one thing I'm trying to understand, like in ICE score there is an impact, and you told that this is an impact on the business. And metrics that we work on are often related to the business like revenue or acquisition or conversion. This is not related to the value for the customers. And on the other hand, you popularized the term of the North Star Metric, which focuses on the value for the customers. Is there any way to combine those metrics, or which metrics should we focus on as a growth team, as a product team, as an organization?

Sean: Yeah, I think they are combined. If you're thinking of the North Star Metric as value to the customer in terms of average value, then you're probably thinking about the North Star Metric wrong. But if you're thinking about it as the aggregate amount of value being delivered to customers, then you take all of the submetrics, like acquisition, and you start to say, well, if I get 10 times as many customers experiencing the product, then I just created 10 times as much aggregate value.

Pawel: I saw the presentation of Itamar Gilad recently, where he described this model in which the product has two functions: one is creating value, and the second is capturing value that you create. So yeah, revenue is capturing value, but then you can reinvest this value to create even more value for the customers.

Sean: Exactly, so it seems very logical that you have this scientific process, you have goals that you mentioned, or metrics that you would like to move, and then you have ideas, you have a backlog of ideas, you have experiments, you run those tests to validate and invalidate your ideas. So what can go wrong? It seems quite simple, easy to understand.

It seems completely simple, and so when I wrote my book, it kind of lays all of this out, and it seems very easy. Teams would read the book, CEOs would read the book, and then they would go and try to do it, and most of them would fail. It turns out that it's not as easy as it looks, and there's a couple of reasons. First is when we talk about that growth engine, we're talking about customer acquisition, customer activation, how do I engage customers, how do I monetize customers, each one of those things tends to be controlled by different teams within the company.

Acquisition might be traditionally controlled by the marketing team, conversion kind of for a lot of companies wasn't really controlled by anybody, it sort of sat in between product and marketing and was not even addressed, but engagement and retention of customers was more of a metric for a core product team, maybe a sales team might have something to do with the Revenue Loop. If it's e-commerce business or something that's completely online, it's going to maybe sit more inside product. And then when you're running these experiments, you often need engineering to help, you need designers to help, you need data people to give you feedback.

What it turns out is that most of these functions within a business are used to operating fairly autonomously from each other. Even if you got a brand new business, it may just mean that they have habits from their old companies where they worked autonomously from each other. But particularly if you've got a 10-year-old business or a 20-year-old business, and you have kind of forms that have grown within the business, it just turns out to be really hard to run experiments across each of these levers.

What you see a lot of times is that like growth marketing will emerge as a discipline, but it's really just pushing that team more and more to the top of the funnel, where now they're just running a marketing function, they just have a different name, it's called growth marketing instead of marketing, but it's still just testing new ways to acquire customers or bring them into the top of the funnel. And so that's where it falls apart.

What I've found really effective for overcoming that cross-functional challenge is to get these functional leads together in the room for a full day to make some of these key decisions. What can they all agree on? Generally, they can agree on who's the customer, what's the need, how are we satisfying that need, what why is what we're doing even important, and starts to kind of come down to the mission side of the business.

Once they agree on the Mission, then they can usually agree on what a North Star Metric should be. Then they can start to move closer to what does the growth engine look like. If they all have their own view, where the sales team is saying the growth engine is entirely a function of what the sales team does, and the marketing team has a different view on what that growth engine looks like, and the product team has a different view, it's going to be really hard to work together.

So they have to come together and combine their perspectives to have a shared vision of how does this business actually grow. Once they're all on the same page, then looking at the growth process and agreeing how they can work together to execute that growth process becomes the next step. Ultimately, it is if you can get the right people in a room together, even if it's just for a couple of hours, but I think a full day tends to be the right amount of time to agree on how they're going to work together effectively to execute this growth process around an engine where they've agreed on what that shared North Star Metric is.

The other thing that I've found that I think is a really common failure point is that you do need one person leading the growth efforts, and so that might often be, you know, just a head of growth role. And getting the right skill set in that head of growth role is really tough because you basically need almost two opposite skills to do it effectively. One of the skills is you need to be really aggressive because you essentially have people who've got their own areas of influence that if you're not aggressive, they're just going to squeeze you out of their area of influence.

So I'm running growth, but I can't do anything with the product, or I'm running growth, but I can't do anything with marketing, I'm running growth that I can't do anything with pricing. So you have to have access to all of those things, but you also have to be then very diplomatic about it. And so if you go in and you just start messing with someone else's area of responsibility and you're not explaining why it's important and you're not getting their input on how to best approach it, then you're going to probably anger a lot of people who would then again squeeze you out.

What I found is that most people are either too diplomatic and then they do nothing, or they're too aggressive and they anger everyone. So you have to kind of find that balance there. So if you do the workshop and you have the right growth leader that's got that balance of diplomatic and aggressive, then I think you've got a pretty good chance of being successful with growth.

Pawel: Can you somehow increase the chances of success, like by setting common goals in the organization or maybe building the right culture? I think building the right culture is the right objective there, but it's really like how do you build the culture? Do you just create a PowerPoint deck that says this is our culture? Or is it something that requires more effort?

Sean: And I think culture is essentially values and habits. So if you have a common set of values and the habits that support those values are consistent with those values, then that starts to become culture. So that's where I think you have to focus on habits before you focus on culture. And the habits are, you know, there's certain things like just the language you use in the business.

We talk about this in Go Practice, the online course that I run with Oleg Yakubov, where you learn the language of hypothesis. Right now, in a lot of companies, people just state their opinions as facts, and that's where a lot of This falls apart. When an opinion is not a fact, state it as a hypothesis. My hypothesis is that people are churning because they're not getting enough value. My hypothesis is that there's a big opportunity in accounting for our product. All of these kind of guesses, if you use the language of hypothesis, then you're much more likely to say, okay, how do we validate that hypothesis or invalidate that hypothesis? And you become a lot more flexible in how you execute.

So, building the right culture can just come down to some of the language things, but ultimately, I think it's the testing habit that builds the culture. And how do you maintain a good testing habit? You need to be able to have reinforcement by getting some wins from those tests. So if you run 20 tests as a team and you put a lot of effort into those tests and none of those tests drive the desired result, you're very unlikely to be able to keep a rigorous testing process going.

So it becomes really important to do that upfront analysis to say, you know, we have a big drop-off in the signup to usage or a big drop-off in people coming back to use after that first time. But wherever that opportunity is, if you can really contextualize it, understand why the behavior you're trying to drive from users is not happening, and then come up with some test ideas based on really good research, you're much more likely to have a higher success rate from those tests.

And that success rate is going to be what reinforces the behavior of the team to keep wanting to run more tests. So, ultimately, it is about having a habit of testing. To keep that habit of testing going, you're going to need a pretty high win rate. Once you do that, then you start to be able to build a culture that is recognizing that we learn through testing and that we use data to inform our decisions. Anything that we don't know as a fact is an opinion, and we refer to them as hypotheses.

Pawel: Amazing. Sean, could you tell me more about the North Star Metric? Why is it important, and why should we track it?

Sean: Basically, if you have the wrong North Star metric, all of this falls apart. So, the right North Star metric is really important. Essentially, what you're trying to do is quantify that product-market fit that we talked about as being so important. Product-market fit is about providing an important value to a specific type of customer. If you can then quantify how much of that value and how many of those customers are, that's going to be a good North Star Metric. Having the right North Star Metric tied to value is going to lead to sustainable growth.

So, if I'm delivering more and more value to the right customers over time, those customers are going to keep coming back, and I'm going to be able to retain those customers. The alternative is that a lot of companies get caught up in just looking at revenue. They're more and more focused on revenue. And if I need to trick customers to generate that revenue, so be it. If I make it really hard to cancel my product, then that's going to keep that revenue going.

If I'm an ad-supported product and I start to put twice as many ads on every page, that's going to help my revenue. But ultimately, if you're hurting the customer experience and the value over time, that revenue is going to disappear.

So, what you want to make sure of is that the amount of value that you're creating over time does not exceed the ramp of your revenue. And so, that's why focusing on a North Star Metric instead of a revenue metric is going to lead to more sustainable growth.

Now, there's another benefit to it, is that revenue tends not to be very motivating for the team in the long run. It's just like it's kind of a cold metric that people don't get excited to jump out of bed to say, "Metric grew by this much," or, "Yeah, just top-line revenue grew by this much." But to be able to say, like, let's say you're a solution that helps people live longer, you know, like, like years added to lives is something that potentially could really be motivating for the team. Or, you know, and maybe not everything is going to be quite to that level.

So even if you're, like, for Uber, they're looking at weekly rides. And so again, the alternative might be, "Oh, I want to look at app downloads." App downloads don't really create value, but knowing that this week, we generated 50 million rides across our network and 50 million people got where they needed to go, you start to kind of feel more of an emotional connection to that than just sort of a pure revenue number. And so I think that's another benefit, is that people connect to the mission a little bit more when it's a metric tied to value.

Pawel: Yeah, I love the distinction, this 'why' perspective. Also, Simon Sinek talks about it a lot - why we are motivated. And that's definitely important for the team, an essential factor, and in startups, like, you need a lot of energy to keep working hard. And if you don't have a strong 'why,' it becomes harder to keep putting that effort and energy into the business.

I have never understood why when you open Google and just look for examples of North Star metrics, the results that you can find present something like revenue or market share as a metric example.

Sean: I think part of it is just people don't necessarily understand what a North Star metric is and why you need it. And so that's the problem with all of this, is that you have kind of differing opinions, and people get upset around terminology, and you know, like ultimately, ultimately, there's, I kind of think of this more as sort of physics, like the physics of growth - how does growth actually work outside of the opinions of how growth works? And we're all working from the same set of physics; it's not like, "I like this physics better than that physics." And then, you know, trying to really understand growth on kind of a scientific level, and then how do you influence it, accelerate it. If you have the wrong understanding of the physics of growth, you're unlikely going to be able to influence and improve it very well if you don't really understand how it works. And so that's where the discussion should be, not on, "Should we call it this or should we call it that?" It should be really, "How does growth actually work?"

Pawel: Okay, so we have a scientific understanding of the principles of growth, how the value exchange happens, and what products are for. And also, we have a scientific process to test our ideas and then sustain this growth.

And how does it all, or maybe it doesn't differ when we are working with B2B products, large accounts, or large contract values where, yeah, you cannot easily penetrate those companies with deals?

Sean: Yeah, so for me, I love consumer for exactly the reason that you have, you usually have a lot more data to work with, shorter sales cycles, you can iterate faster. You know, to me, the nightmare would be I have a market size of 19 potential customers, it's a one-year sales cycle, and, you know, $10 million transactions. That's probably where this approach is not going to add very much value. B2B, yeah, obviously could be anywhere from like a HubSpot, is B2B, but you have a free product, and you know, so that they can have, you know, tens of millions of users on a B2B product, where there's an upgrade cycle from a free version to a paid version. That starts to look a lot more like a consumer. But I do even think that what you are starting to see more and more is that kind of consumerization of enterprise products.

So, in the past, it used to be, "I sell a solution to an enterprise," and half the time, or probably even more than half the time, the person who bought the solution doesn't even pay attention if it gets used. We call that shelfware, and it wasn't even SaaS, so it doesn't matter if it gets used or not; it's just there, and maybe they upgrade when a new version comes out every few years.

What you've started to see, and Slack would be a great example here, is you provide something that's of value to the whole business, but you need to engage and retain users on the product the same way you would with a consumer product. It's just you're defining the market size as the employee base within that company. Like when Slack thinks about what is the aha moment for Slack, what's the point at which Slack becomes valuable enough that the business says, "Oh, this is great, I want to keep this long-term," and it's going to be a function of use.

It's when you have about 2,000 messages in Slack that it comes to life, where you can start to see people using it for their communications, and now the search feature becomes more valuable, and grouping those messages becomes more valuable. So, for Slack, then the big goal is, "I haven't really converted someone to Slack until I get a company to 2,000 messages. How do I get them to 2,000 messages?" Either I significantly improve the average number of messages per person, so if I have a hundred users, and I get them to each send 20 messages, that can get me there, or I can have a thousand users who each send two messages. But, I might as well work both of those – get as many users on there as possible and get as many messages per user as possible, and that's going to get me to those 2,000 messages.

But knowing that they don't really acquire that company until it has provided enough value as a communication platform. So, I think that's what you're seeing, even on big Enterprise deals that you, who are the end-users of the products inside those organizations, and how do I make sure they're getting enough value to stay long-term retained on the product. Now you have the same process of improving those numbers as you would in a consumer product, where you're running some research – "Why don't people send invites for Slack?" "Why don't they respond faster when a message is sent?" What are some experiments that we could run to improve the number of invites or improve the response rate to messages? All of that is going to move you to a point where you are able to attract, retain, and monetize more customers and sustainably grow the customer base.

Pawel: Yeah, great, so the process is not much different. You can use the same method, the same thinking, and the same principles to understand this on an account level.

Sean: Exactly

Pawel: Sean, if people wanted to find you, where can they find you?

Sean: Yeah, so LinkedIn is where I'm putting out most of my content these days. So, just follow me on LinkedIn or connect with me on LinkedIn. But, if you want to learn more about what I'm doing with workshops and some other things, I have a website at seanellis.me, where you can see that.

And I'm about to kick off an around-the-world workshop and speaking tour in January, where I will go to a lot of Asia, South America, Australia, and then later in the year, I'll go to Europe, where I'll work with a number of companies in Europe as well. So, probably more around May or June, I'll head to Europe. But, hopefully, wherever your listeners are, we get a chance to connect in person; otherwise, we've got the big wide virtual world to connect.

Pawel: Okay, I also put some links in the episode description. Thank you, Sean, for joining me today. It was a pleasure.

Sean: Yeah, good to be on, Pawel. Looking forward to seeing this get published.

Pawel (Closing Remarks): Thanks for listening to the Product Compass podcast. Today, we discussed the science of growth with Sean Ellis. Subscribe to my newsletter if you haven't already, hit the like button, and share this episode with others so we can keep learning and growing together. Take care.

Thanks for reading The Product Compass

It’s incredible to learn and grow together! 😊

Have a great weekend and a fantastic week ahead,

Paweł

Thanks Pawel. It'll be very helpful if anyone completes the Time to Value Survey -- the more the merrier, and I'll share what I learn with everyone.